The Plutocrat’s Jubilee

By James Carter

We own all the money—we will own the land

The Courts and the Congress are at our command.

Our fortunes have gone up like beautiful rockets’

We’ve the Dems and the Republican both in our pockets;

And to please the fool people, we make our salam,

And let them choose either—we don’t give a damn!

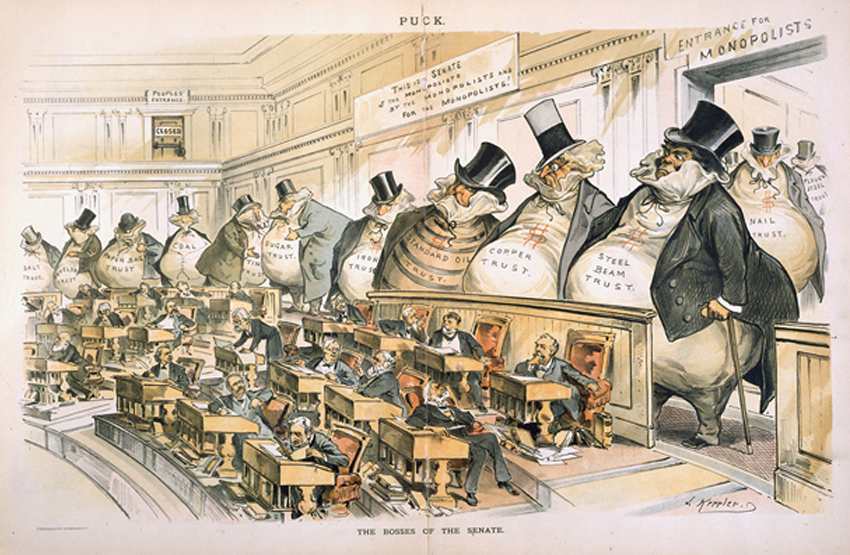

Though perfectly at home in 2017, this little ditty actually dates to the 1890s, a time known as the Gilded Age, when the gap between the rich and poor grew into an unbridgeable chasm. America’s class divide was cast in sharp relief through industrialization of the late 19 century. During these years, the infamous “robber barons” ran roughshod over both government and the people, forging giant financial and industrial monopolies and wringing out of government all the concessions that could be had. Meanwhile, the great many toiled and lived in abject poverty. In the mid-1890s, it all collapsed in the largest and most widespread economic panic in the nation to that point. Tens of thousands of businesses folded, as did more than 500 banks, and millions were pitched out of work and onto the street.

Amid this massive economic depression, groups of ordinary people began gathering as “armies” of the poor and disaffected, and they marched toward the nation’s capital in protest of their plight and against the powerful interests who had come to control the levers of power, as described in the poem above. Perhaps the most famous of these people’s armies, led by Jacob Coxey, was “Coxey’s Army,” a band of several hundred ordinary people who set out from Ohio on a cold, snowy March day in 1894. The army was not Coxey’s idea, but his name stuck to it. Numerous other armies marched around and to Washington, D.C. around the same time. One of them was led by a young Jack London. Others came from Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, Spokane, & Portland, still others from Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, and Utah. Coxey’s Army, numbering some 500, received generous support along the way from ordinary Americans wishing them well. They arrived at D.C. in April. As Coxey approached the Capitol steps to speak to the eager crowd, police rushed in and, beating many in the crowd, arrested him. He and other leaders were charged with walking on the grass. The armies of the poor continued to arrive—eventually over 1,200 came. The authorities still refused to hear them and police scattered the hundreds of demonstrators and forced them to flee.

The thousands of people making up those armies had trekked to D.C. on foot, horseback, or on train, which they rode for free after overpowering guards, all demanded the federal government do more. In particular, they, and Coxey, demanded a good roads bill, an infrastructure bill. Bills had been introduced in the congress calling for the issuance of non-interest-bearing bonds totaling $500,000,000 and paying for improved roads across the nation that would provide jobs for millions of workers. Coming on the heels of the excesses of the Gilded Age, the economic collapse of the 1890s highlighted the plight of the poor and the jobless. Many of the middle and upper classes became convinced of the need for meaningful and sweeping change. It was no accident that the Progressive Era followed on the heels of the Gilded Age. Some of the leading lights of the Progressive reform movement, such as Teddy Roosevelt, recognized at least the political necessity of reform, even if it hurt. Refusing to grant a few rights to working people, as he said, added “immensely to the strength of the Socialist Party.” Others less cynical believed America simply couldn’t go on with a boot firmly on the neck of working people. Reforms such as workman’s compensation, the eight-hour day, increased regulation of corporations and business practices, increased safety in manufacturing jobs, and greater support infrastructure for working people soon followed. Still, significant change, such as the federal law protecting the right or workers to organize, regulation of Wall Street and banks, significant spending on jobs programs and infrastructure, would have to wait for the New Deal during the Great Depression of the 1930s. And, the powerful and the corporations fought it every step of the way.

The recent passage of the tax bill by the Congress should remind us all of the persistence of some of these themes in American history, especially The Plutocrat’s Jubilee. We would do well to remember this as we all react to this most recent transfer of wealth from working and middle-class people to the very wealthy. We would do well to bear in mind that even as Trump’s poll numbers sink ever lower, and even as barely half of self-identified Republicans support the tax legislation, and even as great numbers of people seem to be gathering for a mid-term storm of Democrat triumphs, and even if it really is, as some have lately suggested, the GOP’s swan song, the damage will be enduring. And the plutocrats? No matter. They will have all the bases covered, as they have for a very long time:

We’ve serfs on the railroad, and serfs in the mine,

In the shop, on the farm—all the places, is fine;

And millions in idleness, willing to work

For the pittance we give them, from morning till murk

When we call, round the polls all these fellows will jam,

And vote as we’ll tell them and not care a damn!